In a recent GenomeWeb article by Tony Fong, “Sequenom’s CEO ‘Puzzled’ by Illumina’s Buy of Verinata, Lays out 2013 Goals at JP Morgan,” Harry Hixson, Sequenom’s CEO, expresses puzzlement over why its major supplier, Illumina, is acquiring a Sequenom competitor in Non-Invasive Prenatal Testing (NIPT), and thus apparently competing with one of its major customers.

In a JP Morgan interview on January 8, 2013, Illumina CEO Jay Flatley said:

In terms of our market strategy in NIPT: we plan to leverage the Verify test to drive new applications while continuing to supply instruments and reagents to all the NIPT players. In fact, we are working very hard to reinforce our relationships with our existing customers in this field. We plan to partner to help with distribution of the Verify test, and we intend to outlicense the foundational IP broadly and hopefully through that method expand the market more quickly and resolve some of the underlying uncertainty in this marketplace.

Harry Hixson, Chairman & CEO at Sequenom, comments on the Illumina move in his JP Morgan interview:

I get a call from Jay Flatley and he tells me that he is going to acquire Verinata. And so anyway my mind starts thinking about all of the ramifications of that. We’ve met for two, two and a half days now with analysts, investors and everyone asks us the question, “what do you think this means?”, and then they follow it up with “we don’t understand it”. And I would say at this time that Sequenom is puzzled. I would like to read some quotes from Jay’s press release…. And he also says “we are working very hard to reinforce our relationships with our existing customers in this field”. I might add, I’m waiting for the call – the second call.

Illumina’s move appears to be putting Sequenom in an uncomfortable position, a move that is puzzling both its customers and investment analysts. Is there a clear strategy behind what Illumina is doing?

Two explanations come to mind. (I’m curious if anyone has any other theories?) One is that existing products and markets will not enable Illumina to sustain desired growth and so they are entering new markets, including selling to the customers of their customers. The other is that Illumina is deliberately shaking up a conservative diagnostics market in order to drive demand. That is, Illumina is driving quicker adoption of high throughput sequencing for clinical applications by providing both prenatal testing as well as whole genome sequencing services.

Why is this move so interesting (i.e., why do I care)? Many of us in the bioinformatics world feel the competitive pressure of spending large R&D costs to serve a relatively small market of research scientists whose goal units are generally disconnected from revenue generation. If Illumina has a way to break out of the economic limits of the research market, we want to learn from them. Let’s look at the limits to growth in research genetics.

The Genetics Research Market

Various estimates I’ve seen indicate that Illumina has 70-80% of its revenues coming from academic and government research. This may well be higher, as revenue realized from commercial labs may have a substantial fraction of their volume ultimately serving academic research pursuits. Further, Illumina apparently owns an estimated 80% of the NGS sequencing market (though a recent GenomeWeb article says Life Technologies claims it has 60% of the Desktop Sequencing market).

Given NIH provides most of the dollars for US academic and government research and that the days of steady NIH budget increases appear to be on hold for the foreseeable future, the academic and government research market is unlikely to significantly grow over the next several years.

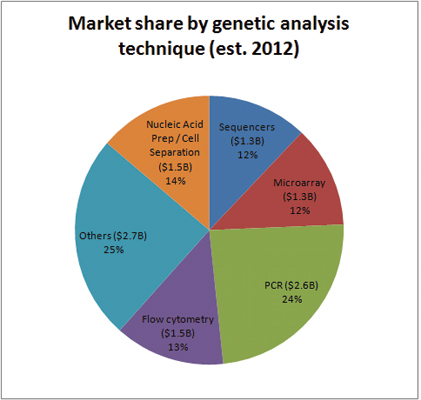

Why is the commercial market such a small proportion of Illumina’s revenue, and must it remain that way? ISI Group, drawing on data from Instrument Business Outlook, shows the total worldwide genetic tools market comprising sequencing, microarrays, PCR, flow cytometry, in-vivo imaging, high content screening and informatics to be an estimated $11B in 2012. This represents about a quarter of the ~$45B life sciences tools industry serving all sectors. According to this same report, 27% of this $45B is academic and government, with 24% biopharma, and the rest made up of hospitals, CROs, and other miscellaneous categories. Sequencers and microarrays make up about 25% of the genetic tools market.

Source: ISI Group, http://www.isigrp.com/main/assets/pdfs/07-09ls.pdf

With microarray spend being displaced by sequencing for both DNA and RNA, and with an increasing proportion of PCR being substitutable by Next Generation Sequencing (NGS), it would appear that there is $5B in market share available for Illumina to fight for. However, even with decent market growth, there is no way for Illumina to continue the 83% compound annual growth rate (CAGR) it sustained over the last 10 years.

Given a fixed spend on experimentation in academic/government life sciences research with flat expected growth, fighting to take market share away from other smart competitors (each fighting for their share of that same sandbox) is an uphill battle. It may give short turn returns, but ultimately you will eventually run up against the physics of a limited market. Perhaps this is why Illumina, and most everyone else in the field of genetics research, is eyeing the greener pastures of clinical genetics or diagnostics.

The Diagnostics Market – Greener Pastures

According to Bloomberg, the total diagnostics market today is around $44B, of which $5.6B is genetic testing. However, when a number like $5.6B is reported by healthcare providers, that is the reimbursable charges made by providers to patients and insurers. Many genetic tests are reimbursed at around $3,000, including cytogenetic assays. Consider, however, that for a cytogenetic microarray based test, an equipment and consumables vendor like Illumina might make $50-$300 for the microarray. Whole exome or genome sequencing is more expensive, but for widespread adoption it will likely have to come in line with being profitable for healthcare providers to order tests for around the current $3,000. So even if you are the provider of supplies for the entire $5.6B market, you might bring in revenues less than 10-20% of that or under $1B. So despite 17% annual growth of that market, the question becomes do you want to be the organization receiving $50-300/test by providing equipment and consumables, or the one receiving $3,000/test by providing the one stop solution reimbursable through health insurance?

Illumina’s 2011 annual report says, “the Company is organized in two operating segments for purposes of recording and reporting our financial results: Life Sciences and Diagnostics… The Company will begin reporting in two reportable segments once revenues, operating profit or loss, or assets of the Diagnostics operating segment exceeds 10% of the consolidated amounts.” They appear to be organized to go after diagnostics – it remains to be seen if it is mainly through hardware and consumables or other business models.

Absent some consumer genetics play, for Illumina to do well by its shareholders and grow from a $1B company to a $10B company in the years to come, it almost seems forced to enter the diagnostic testing market as a laboratory service, instead of just providing the equipment and consumables. It thus seems unavoidable that it will more and more come into conflict with its diagnostic laboratory clients who likewise see the potential of that market.

Supplier Becoming a Competitor

So what does it mean for a company like Sequenom to see their supplier becoming their competitor? Or similarly, what does it mean for a core lab that makes its revenues running samples on Illumina HiSeq instruments to see Illumina providing a CLIA sequencing service for whole genome and tumor normal pair sequencing? While Illumina may downplay that they are not in the space of single gene tests or exomes, ultimately it is expected that more and more testing will converge to whole genome coverage, leading to a future collision.

The main fear is that Illumina as the supplier is in a position to out-compete on price. Normally price is a weak competitive advantage among manufacturers, as the time it takes to match a competitor’s price is negligible, and there is the deterrent of a price war in which nobody wins. However, in the case where one competitor cannot manufacture the goods, but must acquire them from the competition, competition on price becomes viable for the manufacturer with the built-in asymmetric advantage. This will lead to the disadvantaged party searching for alternate suppliers, and thus the rise of additional manufacturing competition who are willing to stick to being suppliers and not selling the diagnostics directly. These will be smaller sequencing hardware companies who initially don’t have the growth limitations of Illumina, but who, if they eventually succeed, will be in the same conundrum Illumina is in now. Illumina could alleviate these fears by being the most expensive CLIA service in the market, but that puts them in conflict with increasing the revenues of their diagnostics operating segment.

On the other hand, perhaps they intend to shake the market just enough to get genetic testing labs to start adopting high throughput sequencing en masse to drive demand, then back off and stick to the fundamentals of selling equipment and consumables, licensing their tests and stepping back to let others do distribution.

Perhaps from a scenario planning standpoint they don’t even have to decide at the outset which strategy they ultimately go with – they can probe and test, and will gain regardless. That is, whether they displace their customers and take the market (in which case those customers are not around to complain), or drive a reactive market surge from customers/competitors that lifts all boats and then back off, smooth ruffled feathers, and reap the rewards of a larger market, it seems like they could win either way.

Like Hixson and investor analysts, I’m also puzzled. What do you think?

Hi Christophe,

Thank you for a nice and detailed post concerning the financials of Illumina and their plans. The question of a supplier becoming a competitor has been happening across many fields where the manufacturer decides that they can do a lot better by cutting out the middle man. To give two examples from the world of computing, Microsoft has introduced tablet computers where it directly competes with other computer makers. But, when they sell a tablet Microsoft gets all of the profit and not just the cost of the Windows OS. Also, consider Apple and their retail stores. Before there were Apple Stores, people would go to either a computer of a big-box store to purchase a Macintosh Computer. Apple realized that they could greatly increase their margins by having their own retail stores where they controlled everything. A sad consequence of this is that most computer stores that specialized in selling Apple products have gone out of business since they cannot compete with Apple.

In the genomics world, the situation with Illumina is very similar. As you mention, they have taken control of the whole genome sequencing market through the Illumina Genome Network (IGN) where the prices they offer are much less than anybody else could match by simply buying a HiSeq and reagents. I think there are many signs that Illumina is acting like a monopolistic company and this is one echo of that. They dropped the prices of whole genomes so low that their only realistic competitor Complete Genomics was forced to sell itself at a fire-sale price to BGI. The low prices of genomes were subsidized by the other businesses that Illumina has whereas Complete Genomics only had one product. But driving Complete Genomics to BGI wasn’t enough, and Illumina wanted to buy them to presumably shut them down and eliminate competition.

This behavior of Illumina, along with what you mention concerning NIPT is very concerning and therefore people are looking for an alternative to challenge Illumina’s dominance. Unfortunately, if one wants to get lots of sequence cheaply and reliably, there are no real current alternative to the HiSeq

Hi Jeffrey,

Thanks for your comments, and drawing the parallels with Microsoft and Apple “cutting out the middle man”.

With Complete Genomics, I don’t know if their problems were so much due to price competition, as they ran into capacity expansion issues — that is sales was not their constraint, but delivery. Further, related to that operational bottleneck, Illumina by selling machines and having their customers run them and take care of their own analysis were able to expand a lot faster than Complete Genomics, which had to resource providing the complete solution. Complete Genomics, at least for some time, had the reputation for the best data, which drove a lot of interest and sales. But their delivery capacity prevented them from having the same virtuous feedback loop Illumina had of rolling revenues back into R&D to create improved and more cost competitive offerings.

Now that Illumina is big enough, it can look up and down the supply chain to try to capture more margin as you suggest in the Apple example.

Life Technologies should still provide Illumina with a significant competitor. It is interesting to see their Claritas Genomics spin-off with Boston Children’s Hospital. It allows them to generate clinical revenues in a separate entity, adding the research hospital component as a differentiator, with a lower chance of ticking off their clinical sequencing customers.

Thanks Jeffery for using the computer shop analogy – I’m using a similar one when trying to explain the biggest gap in consumer understanding of genetic testing: people have low level of technical understanding of genetic testing, which is on par of consumers’ knowledge of computer’s key performance characteristics (RAM, processor and hard drive) in the early days of PCs. In early 80’s “geeks” were early adopters but only specialty computer shops were able to bridge the knowledge gap and alleviate fears of incompetent consumers. I think there is a huge potential for “genetic shops” that could help with marketing, but it is virtually impossible to launch such venture in the shadow of 23andme that works hard to monopolize the DTC market. Unfortunately, lllumina is “colluding” with 23and me by helping to offer the test below cost. In any other industry such practices and subsidies are considered anticompetitive and illegal. But DTC genetic testing is way too small to be on the radar of government…

You can see my rant about this on my blog:

http://blog.fairgene.com/when-prices-fall-too-fast-it-is-a-sure-sign-of-unfair-competition-23andme-and-illumina-against-the-world

In the diagnostic market, traditionally 80% of the revenue goes to the service provider (i.e lab), 20% goes to the tool developers (reagents, equipment, analysis). Therefore, it makes sense for companies like Illumina to go for additional revenue by organizing a separate business unit.

Sequenom itself tried to to do that using their Mass Spec based genotyping technology. (eventually they had to switch to using Illumina as sequencing data is much better than genotypes). Affymetrix tried to set up a diagnostic service and then gave it up after a couple of years. sold the lab to Navigenics).

I even know a German software company who wants to start their CLIA lab in the US to go for the diagnostic money pot.

Therefore, what Illumina is doing is not an unheard practice, but how much success they will have still remains to be seen.

Glad to see my guesstimates were pretty close — is there a good source for this 20% estimate?

Because most of Illumina’s revenues are research, they still have a large base of customers who won’t be offended if Illumina provides low cost lab services. If Illumina wants to go after the clinical market, now is the time, before too much of their customer base sees them as a threat. They might take the lead of LifeTech and spin off separate entities for this. There is a long term trend of hospitals bringing more and more of their tests in house, both as a revenue center, and to accelerate turnaround times. With the advantage of MDs providing advice and care, along with genetic counselling, I’d think turnkey franchises of co-owned genetic testing centers inside hospitals might be the way Illumina and Life Tech ultimately best monetize their technologies in the clinical domain.

Christophe,

Very nice analysis! The field of molecular genetics is so frothy with innovation that business models are changing rapidly as well and picking winners and losers is going to be difficult.

At the end of the day, personalized medicine is here to stay. It is just not clear what information is going to clinically actionable and reimbursable and who is going provide it.

Still plenty of blue ocean for players in this space.

Best,

Lewis

Good to hear from you Lewis!

While specific forecasts are hard to make, there are some predictable structural factors that will hugely influence the future. For instance, if we believe genetics is going to be ever more rapidly integral to the practice of medicine, and we look at the gap between current supply and expected demand of genetics expertise in medicine (for instance there are <1000 board certified medical geneticists in the US), and consider that it might take a decade to mint new experts in the field, there's going to multiple business models arising to try to close that supply demand gap in the years to come.

As you say there is plenty of blue ocean — though I expect more shipwrecks than ships coming in. As I wrote in my blog on the genetics supply chain (https://blog.goldenhelix.com/?p=985), the systemic obstacles to making significant improvements to the health of the end patient remain quite entrenched. Just as the exponential growth of NIH funding has stalled, so too has the growth of percentage of GDP our society will spend on healthcare. I think this represents a phase change in the system — a time of crisis and of opportunity. Lots of creative destruction to look forward to.

Warm regards,

Christophe