An under-utilized use of VarSeq is the ability of mining raw variant data in GenomeBrowse for relevant literature. By bringing in various public and private annotation sources, GenomeBrowse allows the user to interface with raw variant data in a compressed and manageable view. This blog will show you how to leverage these sources to power up your search for variant literature.

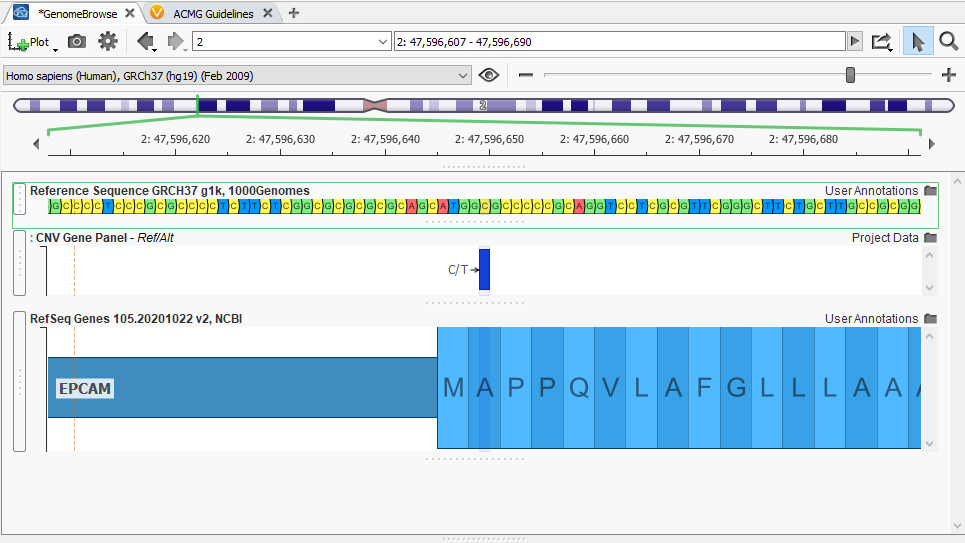

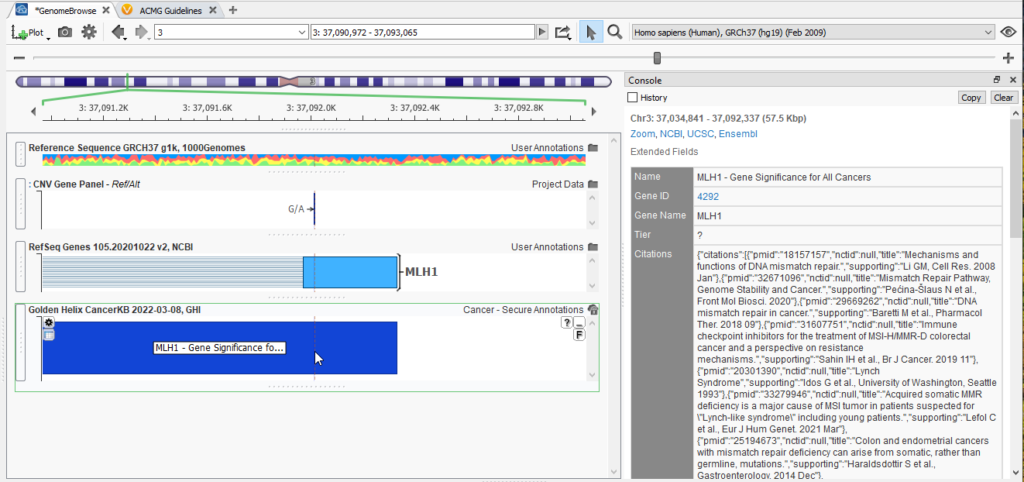

In Figure 1, I have a simple field of view in GenomeBrowse, where I am examining the Reference Sequence, the Ref/Alt designations of the current variant in my sample, along with the gene my variant falls in from the RefSeq Genes track. Other information in this field of view includes the Genome Assembly Build and the chromosome location. By bringing in additional fields and annotation sources, I am able to mine this area for relevant information and literature.

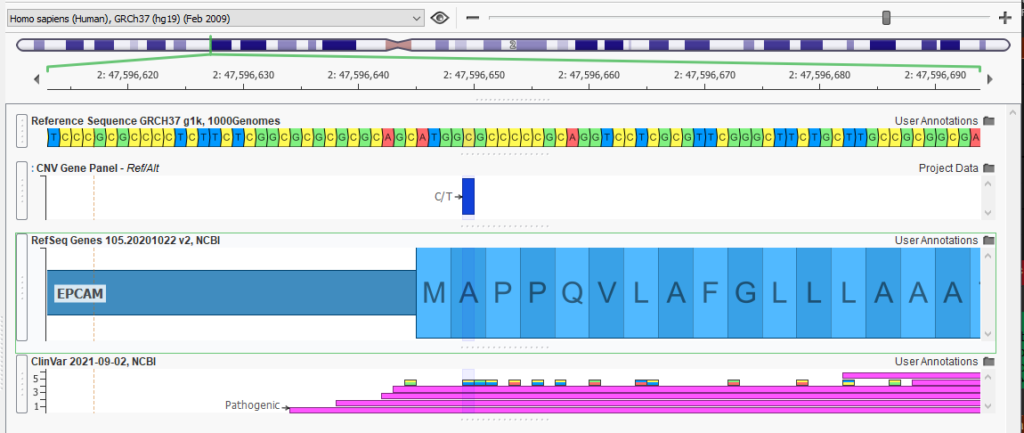

One of our most commonly used annotation sources is ClinVar (Figure 2). This view displays the records for this location, both the single nucleotide variations and the larger regional variants with ClinVar submissions.

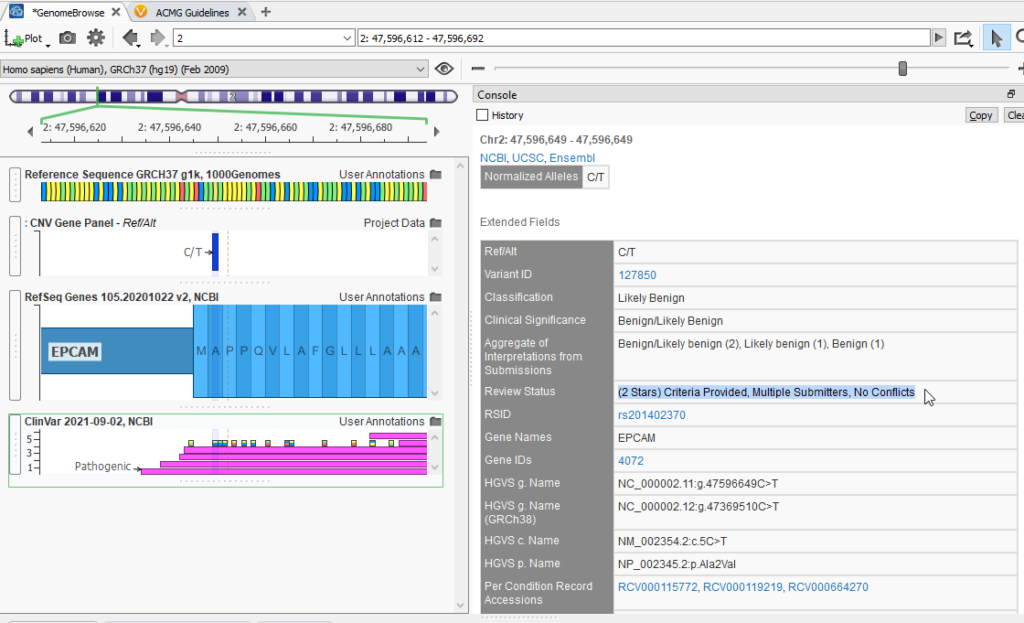

By clicking on the top entry of this list, I can see that there is an entry for my same C/T variant (Figure 3). ClinVar has reviewed this variant, and with a two-star rating, has designated it as benign. Additionally, this console window displays the variant’s associated g., c., and p. notations, along with the rsID and other useful fields.

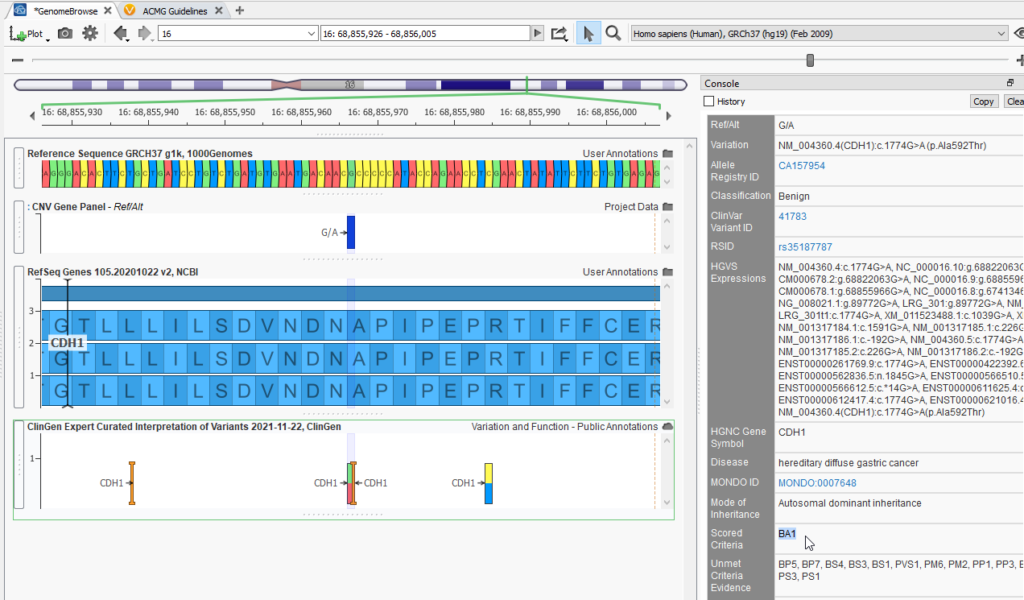

Other annotation sources like ClinGen can provide detailed reviews of specific variants (Figure 4). Here is an entry for a different variant in my project, in the gene CDH1 and the matching ClinGen Expert Curated Interpretation of Variants entry for my variant. The entry lists the classification for this variant as Benign while highlighting the relevant scored criteria and the associated Summary of interpretation for this particular variant.

If the ClinGen Expert Curated Interpretations seem familiar, you may be thinking of our very own CancerKB database. This in-house expert-curated and reviewed database is updated monthly. This database provides information on a growing list of cancer biomarkers and cancer genes. CancerKB can act as the starting point for clinical interpretations by providing descriptions of genes, tumor-specific information, and biomarker summaries. In addition, the most common biomarkers will have associated Tier level and drug information.

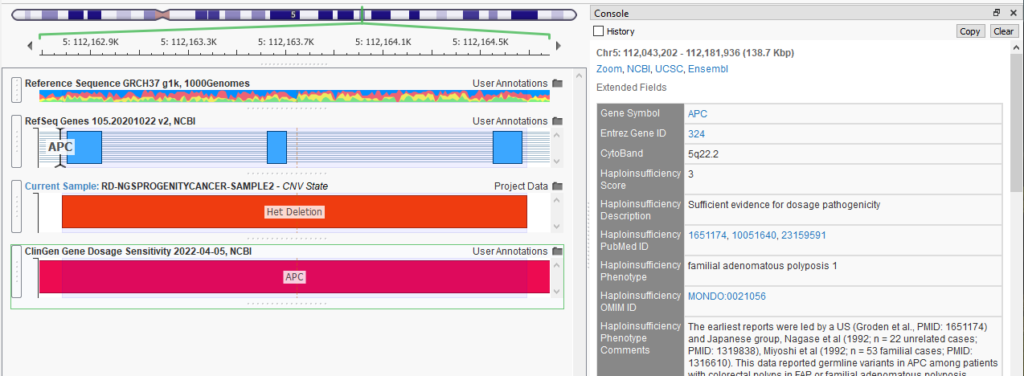

A database with information more specific to CNV analysis is ClinGen Gene Dosage and Sensitivity (Figure 6). ClinGen assesses whether a loss or gain of genomic information will result in a pathogenic state. For example, this Het Deletion appears to be across three exons in the gene APC. ClinGen has surmised that this CNV has a haploinsufficiency score of three with sufficient evidence for dosage pathogenicity. Alternatively, in the case of a duplication, this database can provide information about triplosensitivity.

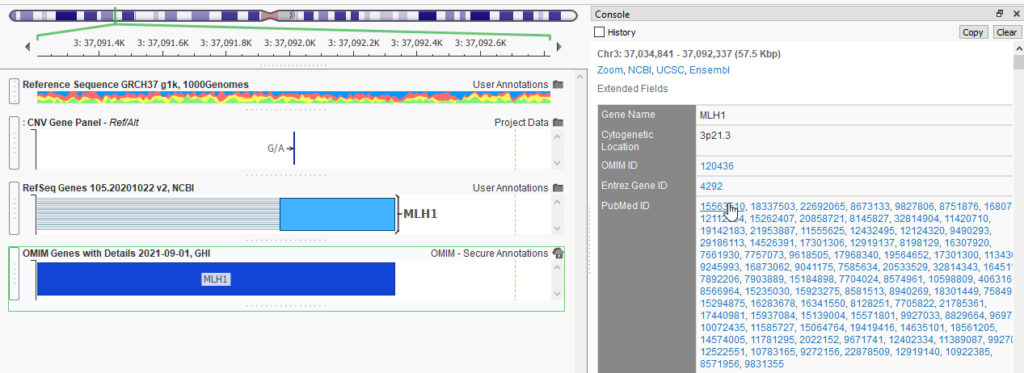

A powerful database to leverage is OMIM, or the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man database (Figure 7). OMIM provides comprehensive overviews of genes and phenotypes, including the complete list of PubMedID publications relevant to the gene of interest.

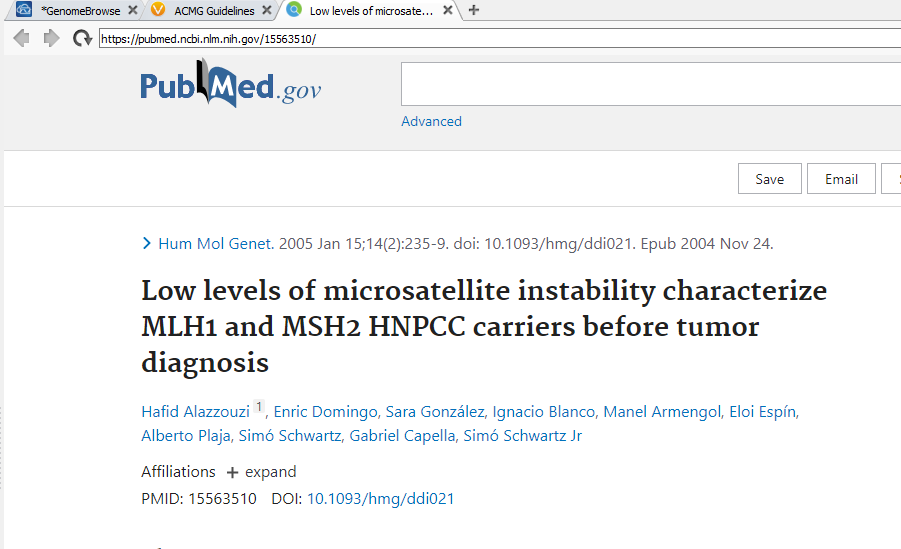

This makes it a breeze to deep dive into the literature without having to search for the papers through Pubmed. Here in the right-hand side of Figure 7, I can click on any of the PubMedIDs, which pulls up the VarSeq internal web browser for easy reading (Figure 8).

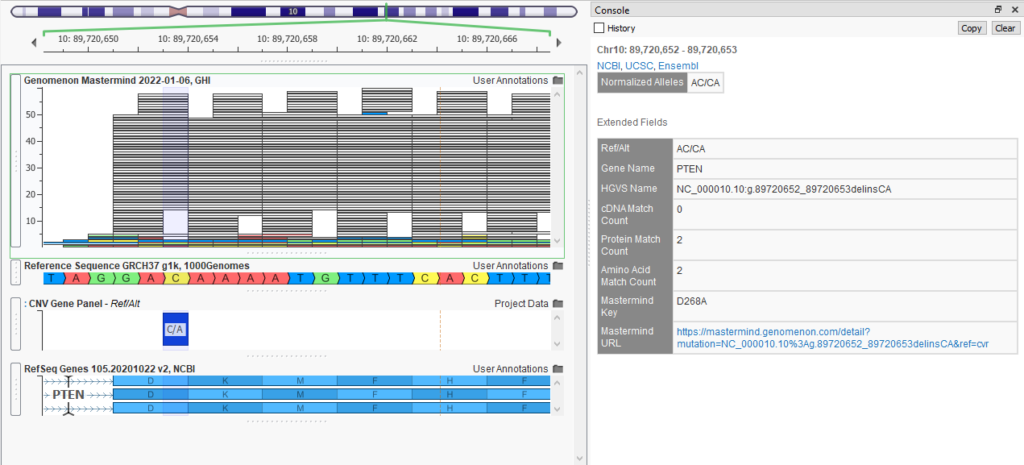

While OMIM will provide literature relevant to the gene of interest, the last database I will showcase today is Genomenon Mastermind which specializes in per variant data (Figure 9). The abundance or lack of associated medical literature can be leveraged to look for clinical actionability.

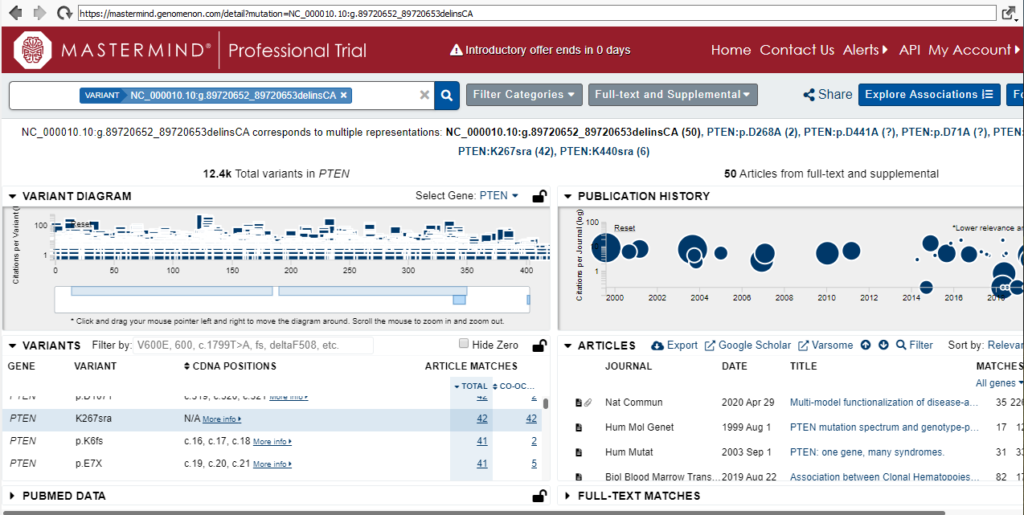

Clicking on the Mastermind URL brings up the web browser page that lists the total number of recorded variants in that gene, supported articles, and publication history, making it easy to look for the most recent literature (Figure 10).

Here I have demonstrated, starting with raw variant data, how to mine literature relevant to both my gene and my specific variant by accessing different annotation sources and databases with GenomeBrowse. Although this has been an incomplete view of the tools available with GenomeBrowse, we have covered several of our favorite data sources. Now that you have your relevant literature, the next step is to analyze your data. The ability to streamline the interpretation of this data comes through the use of VSClinical, which we will highlight next. Stay tuned, and in the meantime, if you would like to know any more about access to these databases and annotation sources, feel free to send an email to [email protected] and we will be happy to help.